This is the aesthetic of southern America. This is the heart of the monster, the birthplace of Coca-Cola and the fast food chain – and for every franchise that launched its spawn across the globe, there are a dozen that never made it out of the south. They remain here with their wacky names and neon signs, their curious not-quite-so-well-formulated menu concepts, relics from a bygone era of American cultural imperialism.

This is the aesthetic of southern America. This is the heart of the monster, the birthplace of Coca-Cola and the fast food chain – and for every franchise that launched its spawn across the globe, there are a dozen that never made it out of the south. They remain here with their wacky names and neon signs, their curious not-quite-so-well-formulated menu concepts, relics from a bygone era of American cultural imperialism. Hardee’s promises us “charbroiled burgers”, an unappetising process that sounds like boiling burnt meat. There’s Sub Station II, which never fully explains what became of its predecessor. Miami Subs & Grill crawled as far north as South Carolina, but no further. Dairy Dream did even worse than the chain it sought to emulate. On its sign Taco Bell asks us “Why pay more?” A question easily answered by anyone who has actually eaten their product.

MY COUSIN Gabriel took me for a drive in his father’s pick-up truck along Two Notch Road, a choked thoroughfare that carries the majority of the mall traffic. Even ten years ago, during my last visit, this road bore on its flanks parking lot-after-parking lot, anterooms to the big box cathedrals of consumerism. Now the shopping sprawl extends miles and miles beyond its former boundary as development pushes further out into the suburbs.

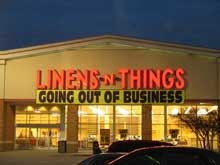

The mushrooming megamalls are an illusion of prosperity, however, for the represent the replacement, not duplication, of retail outlets. On the other side of town stands the Richland Fashion Mall, a multi-level modern facility that a decade ago housed several department stores and hundreds of smaller boutiques. Today it is a ghost mall. All but one of the department stores and a handful of boutiques remain. It’s a scene repeated at Columbia Mall, which was the bustling heart of the north-east side of town – now abandoned to the discount retailers. All across Columbia stand the hulking frames of decommissioned big box outlets, and, nearby, the instantly-recognisable shells of closed fast food joints. The corporations that inflicted this visual pollution on the suburban landscape have departed for more profitable locations, leaving their legacy of architectural decay.

The mushrooming megamalls are an illusion of prosperity, however, for the represent the replacement, not duplication, of retail outlets. On the other side of town stands the Richland Fashion Mall, a multi-level modern facility that a decade ago housed several department stores and hundreds of smaller boutiques. Today it is a ghost mall. All but one of the department stores and a handful of boutiques remain. It’s a scene repeated at Columbia Mall, which was the bustling heart of the north-east side of town – now abandoned to the discount retailers. All across Columbia stand the hulking frames of decommissioned big box outlets, and, nearby, the instantly-recognisable shells of closed fast food joints. The corporations that inflicted this visual pollution on the suburban landscape have departed for more profitable locations, leaving their legacy of architectural decay.Trundling ahead of us in traffic is an empty MTA bus. Comically, the bus is designed to resemble an old trolley car. The irony is that Columbia has never had an effective public transport system – bus, trolley car or train – and the transit options that do exist are shunned by citizens (particularly the white folk) out of class stigma. It’s an automobile or nothing in this town – one for every family member, preferably.

It’s not as if the city has no options – they just chose to ignore them. For instance, Columbia is criss-crossed by railway corridors, most of them used by freight trains. With a little tinkering, these tracks could be put to use for suburban commuter trains. Whenever I offered this suggestion to a Columbian, they would return a blank look that sought to ask “Why? We’re perfectly happy in our cars.”

The blossoming suburbs of Columbia are examples of another curious trend in urban development – the commoditization of location names. In the past, our town and suburb names reflected something about the local area – the history, the environment, the settling families, notable events, national leaders. Today place names are determined by developers whose primary interest is selling land. They chose names that will sound appealing in advertisements. Thus, Columbia is home to Windmill Orchard (where no windmill or orchard ever stood), North Trace, Wildewood, Spring Valley, and so on. Surely developers should be required to adopt more reflective names.

Columbia, like many American cities, suffers from dead heart syndrome. The redbrick downtown has long been abandoned for the ‘burbs. Main Street, the only semblance of a community-friendly streetfront, is home to several wig shops, ghostly bank buildings and little else. I wonder if the prevalence of giant church auditoriums across the city is a reaction to the loss of human-oriented city planning. With no interactive streets, plazas or parks in which to meet, people flock to the ostentatious modern cathedrals in search of some sense of community.

On the last day of my visit to my relatives, the New York Times ran a front page story featuring Columbia as a “snapshot of America’s economic woes." I didn’t come into contact with anyone yet affected by rising unemployment, but I saw plenty of signs of social decay.

No comments:

Post a Comment