THE TRAFFIC in New York is eerily quiet. There’s a $350 fine for horn-honking, so nobody makes a sound. Thousands of automobiles move about silently, like schools of fish through an aquarium.

Scott steers calmly through the streets of downtown Manhattan with a mobile phone glued to his ear. This is a man who knows everybody, and takes time to talk to all of them. Short, wiry-haired, with glasses and animated hands, Scott charms everyone he meets. Nobody is unimportant to him, despite his huge list of contacts. Which is why he can drive into any city and find friends on any street corner.

Scott steers calmly through the streets of downtown Manhattan with a mobile phone glued to his ear. This is a man who knows everybody, and takes time to talk to all of them. Short, wiry-haired, with glasses and animated hands, Scott charms everyone he meets. Nobody is unimportant to him, despite his huge list of contacts. Which is why he can drive into any city and find friends on any street corner.

He did exactly that when we drove in to Boston’s Chinatown, looking for a vegan Thai restaurant. We had just rolled down the I-95 from Portland, Maine, a trip made entertaining by Scott’s expounded theories on the economic forecast for 2009 (“Nobody knows what will happen… The biggest corporations and governments in existence could completely implode… It’s a very exciting time.”). Upon parking his van in a sidestreet, Scott walked less than a block through Chinatown before stumbling upon an entire party of acquaintances, who we then joined for dinner (They were a group of middle-aged peace activists, among them were some of the founders of the Food Not Bombs movement). (After dinner we were invited to a hipster party in Jamaica Plain where white kids danced around to treble-heavy electro music, and a drunk college girl told me: “I just got laid off – I feel like an NPR news story.”)

It happens again in New York as we drift through SoHo at 9pm on a cold Saturday. We stop at a set of lights between Little Italy and Chinatown. A young man and woman wearing santa hats stand lighting cigarettes on the street corner. I’m not even surprised when Scott pops open his door (his window is broken) and yells hello to the man. The pair strikes up a conversation as I laugh silently at the magnetism and sheer luck that surrounds this man. “I’m beginning to think this is all some kind of set-up,” I tell him, as we steer into a parking spot. Scott’s friend has invited us inside a nearby shop. We head inside.

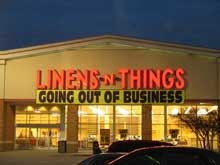

THE SHOP IS called The 1929, named after the year of the Great Depression. It’s a pop-up store opened by a trio of rebellious Hassidic Jews who are an example of the kind of culture that has been inspired by the not-so-tragic economic collapse. As landlords struggle to sell or lease property, they are more open to allowing young artists to use their spaces for temporary projects. Fast-talking Aaron Genuth tells me they conceived the store four weeks ago, and after a two-week crash renovation, they opened. The 1929 sells clothing and art from local designers, and downstairs it hosts art shows and parties.

THE SHOP IS called The 1929, named after the year of the Great Depression. It’s a pop-up store opened by a trio of rebellious Hassidic Jews who are an example of the kind of culture that has been inspired by the not-so-tragic economic collapse. As landlords struggle to sell or lease property, they are more open to allowing young artists to use their spaces for temporary projects. Fast-talking Aaron Genuth tells me they conceived the store four weeks ago, and after a two-week crash renovation, they opened. The 1929 sells clothing and art from local designers, and downstairs it hosts art shows and parties.

“You’re going to see more of this kind of culture as the shock sets in,” Scott predicts, “The economy is put-a-fork-in-it done, and people are finding new ways to do things.”

I MET SCOTT at The Dooryard in Portland, where he was hosting The Lost Film Fest, a travelling video presentation of underground films and clips. Scott acts as VJ and MC during the presentation, explaining the significance of each video and enlightening his audience.

Scott was one of the people behind the infamous New York Times prank several months ago, during which thousands of fake newspaper issues were handed out across Manhattan.

He agreed to give me a ride down the I-95 to New York the following day.

BACK IN NEW York a week later, I check into a cheap flop-house on the Lower East Side at the foot of the Williamsburg Bridge. Not satisfied with the security of my luggage, I walk it around to The 1929 store, the pop-up shop on the corner of Mott and Broome Streets. Aaron greeted me warmly and invited me to hang out for the night.

The creatively-decorated shop quickly fills up with a cast of funky characters, all somehow connected to the boys’ energetic circle. Lapsed Hassidic Jews, models, designer, comedians, authors – it was impossible to guess who would walk in next. The most enthusiastic among them was Levi Ukunov, a frizzy-haired guy of about 27 who speed-read my magazine and told me “I love it, I love it, it’s fantastic,” then sweet-talked me into helping him distribute to Europe his hot new design item – bubbly raincoats stuffed with goose down. The cartoony jackets were flying out the door of their hastily-renovated temporary store. Levi is another person excited by the opportunities created by the economic shift. He has just opened a small workshop in Brooklyn manufacturing clothes.

The creatively-decorated shop quickly fills up with a cast of funky characters, all somehow connected to the boys’ energetic circle. Lapsed Hassidic Jews, models, designer, comedians, authors – it was impossible to guess who would walk in next. The most enthusiastic among them was Levi Ukunov, a frizzy-haired guy of about 27 who speed-read my magazine and told me “I love it, I love it, it’s fantastic,” then sweet-talked me into helping him distribute to Europe his hot new design item – bubbly raincoats stuffed with goose down. The cartoony jackets were flying out the door of their hastily-renovated temporary store. Levi is another person excited by the opportunities created by the economic shift. He has just opened a small workshop in Brooklyn manufacturing clothes.

Later, while sitting on couches in the basement, I overhear a discussion about a project to take over a large building in New York as a green zone, disconnect it from the power grid and power it with solar and wind generators, and run it as a performance space. New York suddenly seems a lot more interesting than the over-moneyed self-important city it was a year ago.

On the train to JFK Airport, I think about the characters I have met during my three-week visit and the inspiration they have provided me. I think also about my money woes – a frozen credit card, five dollars cash and no way to get home from Amsterdam to Berlin. I think about the humiliating email I sent to my brother asking for a money transfer – this after a week in which I lost $400 cash, flew a hitch-hiking sign on the way out of Charlotte Airport, ate (delicious) dumpster-rescue food, stopped to pick up roadkill, and survived 18 out of 20 nights in the hospitality of strangers, friends and family. “You have such a free life,” two people told me this week. Free, yes – cheap, poor, enjoyable, unpredictable. As long as you don’t mind lowering your standards of comfort and luxury a little. The pay-off is a life less ordinary.

...Read more

It happens again in New York as we drift through SoHo at 9pm on a cold Saturday. We stop at a set of lights between Little Italy and Chinatown. A young man and woman wearing santa hats stand lighting cigarettes on the street corner. I’m not even surprised when Scott pops open his door (his window is broken) and yells hello to the man. The pair strikes up a conversation as I laugh silently at the magnetism and sheer luck that surrounds this man. “I’m beginning to think this is all some kind of set-up,” I tell him, as we steer into a parking spot. Scott’s friend has invited us inside a nearby shop. We head inside.

THE SHOP IS called The 1929, named after the year of the Great Depression. It’s a pop-up store opened by a trio of rebellious Hassidic Jews who are an example of the kind of culture that has been inspired by the not-so-tragic economic collapse. As landlords struggle to sell or lease property, they are more open to allowing young artists to use their spaces for temporary projects. Fast-talking Aaron Genuth tells me they conceived the store four weeks ago, and after a two-week crash renovation, they opened. The 1929 sells clothing and art from local designers, and downstairs it hosts art shows and parties.

THE SHOP IS called The 1929, named after the year of the Great Depression. It’s a pop-up store opened by a trio of rebellious Hassidic Jews who are an example of the kind of culture that has been inspired by the not-so-tragic economic collapse. As landlords struggle to sell or lease property, they are more open to allowing young artists to use their spaces for temporary projects. Fast-talking Aaron Genuth tells me they conceived the store four weeks ago, and after a two-week crash renovation, they opened. The 1929 sells clothing and art from local designers, and downstairs it hosts art shows and parties.“You’re going to see more of this kind of culture as the shock sets in,” Scott predicts, “The economy is put-a-fork-in-it done, and people are finding new ways to do things.”

I MET SCOTT at The Dooryard in Portland, where he was hosting The Lost Film Fest, a travelling video presentation of underground films and clips. Scott acts as VJ and MC during the presentation, explaining the significance of each video and enlightening his audience.

Scott was one of the people behind the infamous New York Times prank several months ago, during which thousands of fake newspaper issues were handed out across Manhattan.

He agreed to give me a ride down the I-95 to New York the following day.

BACK IN NEW York a week later, I check into a cheap flop-house on the Lower East Side at the foot of the Williamsburg Bridge. Not satisfied with the security of my luggage, I walk it around to The 1929 store, the pop-up shop on the corner of Mott and Broome Streets. Aaron greeted me warmly and invited me to hang out for the night.

The creatively-decorated shop quickly fills up with a cast of funky characters, all somehow connected to the boys’ energetic circle. Lapsed Hassidic Jews, models, designer, comedians, authors – it was impossible to guess who would walk in next. The most enthusiastic among them was Levi Ukunov, a frizzy-haired guy of about 27 who speed-read my magazine and told me “I love it, I love it, it’s fantastic,” then sweet-talked me into helping him distribute to Europe his hot new design item – bubbly raincoats stuffed with goose down. The cartoony jackets were flying out the door of their hastily-renovated temporary store. Levi is another person excited by the opportunities created by the economic shift. He has just opened a small workshop in Brooklyn manufacturing clothes.

The creatively-decorated shop quickly fills up with a cast of funky characters, all somehow connected to the boys’ energetic circle. Lapsed Hassidic Jews, models, designer, comedians, authors – it was impossible to guess who would walk in next. The most enthusiastic among them was Levi Ukunov, a frizzy-haired guy of about 27 who speed-read my magazine and told me “I love it, I love it, it’s fantastic,” then sweet-talked me into helping him distribute to Europe his hot new design item – bubbly raincoats stuffed with goose down. The cartoony jackets were flying out the door of their hastily-renovated temporary store. Levi is another person excited by the opportunities created by the economic shift. He has just opened a small workshop in Brooklyn manufacturing clothes.Later, while sitting on couches in the basement, I overhear a discussion about a project to take over a large building in New York as a green zone, disconnect it from the power grid and power it with solar and wind generators, and run it as a performance space. New York suddenly seems a lot more interesting than the over-moneyed self-important city it was a year ago.

On the train to JFK Airport, I think about the characters I have met during my three-week visit and the inspiration they have provided me. I think also about my money woes – a frozen credit card, five dollars cash and no way to get home from Amsterdam to Berlin. I think about the humiliating email I sent to my brother asking for a money transfer – this after a week in which I lost $400 cash, flew a hitch-hiking sign on the way out of Charlotte Airport, ate (delicious) dumpster-rescue food, stopped to pick up roadkill, and survived 18 out of 20 nights in the hospitality of strangers, friends and family. “You have such a free life,” two people told me this week. Free, yes – cheap, poor, enjoyable, unpredictable. As long as you don’t mind lowering your standards of comfort and luxury a little. The pay-off is a life less ordinary.

No comments:

Post a Comment