THE WALK from the roadside to Josh and Mel’s cabin is a slippery stumble down a steep track. The hillside is thick, the path invisible underfoot. The entrance to the track is shielded from view, just as the hut itself is hidden behind thick stands of rivercane. They are squatting the land, and would prefer their occupancy to go unnoticed. The hut itself is tiny – perhaps four meters by three, with a single bed, a bench and stove, and a thin strip of floor space. Tonight it’s warm out, even in the week before Christmas.

Josh produces a cardboard carton full of dumpster-rescued food. Dumpsters are their primary source of food, as well as roadkill, forest plants, and the occasional café meal.

Josh produces a cardboard carton full of dumpster-rescued food. Dumpsters are their primary source of food, as well as roadkill, forest plants, and the occasional café meal.

Supermarkets in the US dispose of products at their “sell-by” date, which is often a week before the used-by date. Perfectly edible food gets sent to the dumpster. Tonight they have procured tuna steaks and vegetables, which Josh concocts into a spicy curry, served up with potent home-fermented sauerkraut. We talk into the night of their plans to squat a national forest, living off the land in shelters made from tree bark. They want to move soon, despite the onset of winter. Josh says it is important to get to know the terrain while it is stark and bare, before it is hidden by spring’s verdant cloak. Before the rhododendron grow as thick as walls. He tells me of the botanical history of the region, the native knowledge of the land, of introduced species which have choked ecology. Mel tells me of her fascination with birdsong, how she taught herself to identify the birds of the Blue Ridge Mountains, and can recognize the arrival of migratory species by the change in their tune.

As we fall asleep, Josh tells me that the food pyramid doesn’t represent the true dietary requirements of the human body. It’s a capitalist agrarian plot to make Americans buy certain foods, he insists. I fall asleep on a pallet of blankets on the floor, listening to mice scratching a home in the roof of the hut.

I MET MEL in Tallinn two summers ago. It was a glorious protracted season of warm days and long twilight nights. She occupied the attic of a hostel I frequently visited. We became friends as we played country music together – she on ukulele, me singing badly. A real hobo, she told me stories of riding through the Rocky Mountains in an open carriage of a freight train. She embodies the alternate voice of that country – one that speaks for a return to the land, to share, to create, to care. She informed me of the existence of towns like Asheville, little pockets of resistance against greed-based culture. When I learned of my impending research trip to the US, I promptly emailed her to request an immersion into her lifestyle.

THE NEXT DAY we visit Caleb’s House, a large comfortable wood-floored house in a quiet forested outskirt suburb of Asheville near the banks of the French Broad River. The house is at the bottom of a long country road which twists up the folds of the Blue Ridge Mountains, a name well deserved by those beautiful hazy hills.

Caleb's House is somewhat of a drop-in centre for a large group of Asheville locals. They come here to cook their dumpster-rescued food, to skin the hides of deer which they sew into clothing (see photo, right) to chill-out, play music, and to sleep. Dozens of large glass jars filled with mysteriously coloured liquids bubble away on the benches – batches of moonshine, fermenting and belching (see photo, below). Outside in the yard, the air is piquant with the whiff of rotting meat from the deer carcasses hanging on tree branches.

Caleb's House is somewhat of a drop-in centre for a large group of Asheville locals. They come here to cook their dumpster-rescued food, to skin the hides of deer which they sew into clothing (see photo, right) to chill-out, play music, and to sleep. Dozens of large glass jars filled with mysteriously coloured liquids bubble away on the benches – batches of moonshine, fermenting and belching (see photo, below). Outside in the yard, the air is piquant with the whiff of rotting meat from the deer carcasses hanging on tree branches.

Caleb is the caretaker of the house. He is bound to a wheelchair after a felled tree crushed his legs in the woods. A series of ramps help him traverse the yard. With his house open to friends and strangers, he is never short of help if he needs it.

I curl up on the couch with a glass of invigorating kombucha tea, and read about passive resistance through food in the book “The Revolution Will Not Be Microwaved” by Sandor Katz. People across the US are fighting against the standardization of their food through rules and regulations that were introduced to protect people against poor food quality, but have now begun to have the opposite effect: Collectives of unpasteurised milk drinkers, home baking circles, roadkill eaters (nearly all meat is safe as long as you cook it long enough), and seed savers (a fascinating movement of people working against the corporate ownership of seed varieties). Two dogs lie at my feet as I read, the Blue Heeler pup Satchel, who chews my socks, and the large and lazy Bob, a Wolf cross-breed.

I curl up on the couch with a glass of invigorating kombucha tea, and read about passive resistance through food in the book “The Revolution Will Not Be Microwaved” by Sandor Katz. People across the US are fighting against the standardization of their food through rules and regulations that were introduced to protect people against poor food quality, but have now begun to have the opposite effect: Collectives of unpasteurised milk drinkers, home baking circles, roadkill eaters (nearly all meat is safe as long as you cook it long enough), and seed savers (a fascinating movement of people working against the corporate ownership of seed varieties). Two dogs lie at my feet as I read, the Blue Heeler pup Satchel, who chews my socks, and the large and lazy Bob, a Wolf cross-breed.

Several characters pass through the Caleb's House during the day, which is warm but wet enough to keep us indoors. They wear patchwork clothes and hand-stitched hides. They come from all across America, but have found new homes in rural communities (like the queer eco-farms in Tennessee, Ida and Short Mountain Sanctuary), and float between free-thinking oases like Asheville, Olympia, the two Portlands and New Orleans.

I hear many stories about New Orleans: After Hurricane Katrina, thousands of punk kids travelled down to Louisiana to help clean up the mess. Many arrived before the National Guard or FEMA. Unofficial collectives did the majority of the work in the Ninth Ward, while the government squabbled over jurisdiction and responsibility. In the months and years that have followed, waves of young people have landed in the city to lend a hand. They talk about “Katrina mud,” the putrid sludge of sewerage, river silt and pollutants they scooped and carried bucket-by-bucket. They remember the plastic smell of the FEMA trailers, the shoddy and overpriced emergency shelter vans sent in as temporary housing. In some locations, they were parked row-by-row, surrounded by wire and kept under floodlights – America’s own refugee camps.

“I don’t think any other city would have drawn such a response,” Mel tells me. “New Orleans was a very important cross-over point for travelling folk. We had all spent time there, or had friends who did.”

“STOP THE CAR! I spotted a possum back there,” says Mel. She jumps out of the passenger side door and jogs up the mountain road to fetch her claim. It was the first piece of roadkill we found during our afternoon drive through the rollercoaster hill roads of

“STOP THE CAR! I spotted a possum back there,” says Mel. She jumps out of the passenger side door and jogs up the mountain road to fetch her claim. It was the first piece of roadkill we found during our afternoon drive through the rollercoaster hill roads of Madison County

She returns with a rather toothy looking black-and-white creature.America Australia

The possum is hung in the tree back at Caleb’s house for later butchering, alongside several deer carcasses rescued from the dumpster of a nearby slaughterhouse.

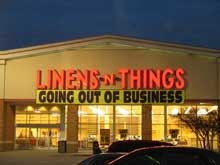

LATER WE LOITER in Asheville’s main streets. It’s refreshing to see a community centre retained in the face of the Wal-Martization of America. We stop in at a bookshop to read zines, and then hang around the co-op food store talking to locals. We head to ‘the bins’, the discount per-kilo Goodwill outlet, where Mel finds some wool clothes for her forest-dwelling season (see photo, right).

LATER WE LOITER in Asheville’s main streets. It’s refreshing to see a community centre retained in the face of the Wal-Martization of America. We stop in at a bookshop to read zines, and then hang around the co-op food store talking to locals. We head to ‘the bins’, the discount per-kilo Goodwill outlet, where Mel finds some wool clothes for her forest-dwelling season (see photo, right).

Our last stop of the night is the dumpster of an organic supermarket. Josh and Mel strap on headlamps and start pulling out bags of rubbish, tearing them open and digging through the trash. I stand by, wanting to help, but restrained by first-timer’s fright. I’ve seen the food they have at home – the unspoilt meats and vegetables, barely-stale bread loaves and just-overdue dairies, from which they create the most delicious and wholesome meals. But this dumpster session yields nothing but true rubbish, to my sensitive eyes anyhow. Josh finds about a kilo of shredded pork, unwrapped and flecked with chewing tobacco. He picks off the tobacco, sniffs at it, and declares it edible. At that point I feel uncomfortable and slink back to the car to wait.

Later, when they cook and serve dinner, Josh gives me a pork-free portion of vegetables he cooked separately. I’m sure they’re secretly offended at my comfortable city lifestyle.

...Read more

As we fall asleep, Josh tells me that the food pyramid doesn’t represent the true dietary requirements of the human body. It’s a capitalist agrarian plot to make Americans buy certain foods, he insists. I fall asleep on a pallet of blankets on the floor, listening to mice scratching a home in the roof of the hut.

I MET MEL in Tallinn two summers ago. It was a glorious protracted season of warm days and long twilight nights. She occupied the attic of a hostel I frequently visited. We became friends as we played country music together – she on ukulele, me singing badly. A real hobo, she told me stories of riding through the Rocky Mountains in an open carriage of a freight train. She embodies the alternate voice of that country – one that speaks for a return to the land, to share, to create, to care. She informed me of the existence of towns like Asheville, little pockets of resistance against greed-based culture. When I learned of my impending research trip to the US, I promptly emailed her to request an immersion into her lifestyle.

THE NEXT DAY we visit Caleb’s House, a large comfortable wood-floored house in a quiet forested outskirt suburb of Asheville near the banks of the French Broad River. The house is at the bottom of a long country road which twists up the folds of the Blue Ridge Mountains, a name well deserved by those beautiful hazy hills.

Caleb's House is somewhat of a drop-in centre for a large group of Asheville locals. They come here to cook their dumpster-rescued food, to skin the hides of deer which they sew into clothing (see photo, right) to chill-out, play music, and to sleep. Dozens of large glass jars filled with mysteriously coloured liquids bubble away on the benches – batches of moonshine, fermenting and belching (see photo, below). Outside in the yard, the air is piquant with the whiff of rotting meat from the deer carcasses hanging on tree branches.

Caleb's House is somewhat of a drop-in centre for a large group of Asheville locals. They come here to cook their dumpster-rescued food, to skin the hides of deer which they sew into clothing (see photo, right) to chill-out, play music, and to sleep. Dozens of large glass jars filled with mysteriously coloured liquids bubble away on the benches – batches of moonshine, fermenting and belching (see photo, below). Outside in the yard, the air is piquant with the whiff of rotting meat from the deer carcasses hanging on tree branches.Caleb is the caretaker of the house. He is bound to a wheelchair after a felled tree crushed his legs in the woods. A series of ramps help him traverse the yard. With his house open to friends and strangers, he is never short of help if he needs it.

I curl up on the couch with a glass of invigorating kombucha tea, and read about passive resistance through food in the book “The Revolution Will Not Be Microwaved” by Sandor Katz. People across the US are fighting against the standardization of their food through rules and regulations that were introduced to protect people against poor food quality, but have now begun to have the opposite effect: Collectives of unpasteurised milk drinkers, home baking circles, roadkill eaters (nearly all meat is safe as long as you cook it long enough), and seed savers (a fascinating movement of people working against the corporate ownership of seed varieties). Two dogs lie at my feet as I read, the Blue Heeler pup Satchel, who chews my socks, and the large and lazy Bob, a Wolf cross-breed.

I curl up on the couch with a glass of invigorating kombucha tea, and read about passive resistance through food in the book “The Revolution Will Not Be Microwaved” by Sandor Katz. People across the US are fighting against the standardization of their food through rules and regulations that were introduced to protect people against poor food quality, but have now begun to have the opposite effect: Collectives of unpasteurised milk drinkers, home baking circles, roadkill eaters (nearly all meat is safe as long as you cook it long enough), and seed savers (a fascinating movement of people working against the corporate ownership of seed varieties). Two dogs lie at my feet as I read, the Blue Heeler pup Satchel, who chews my socks, and the large and lazy Bob, a Wolf cross-breed.Several characters pass through the Caleb's House during the day, which is warm but wet enough to keep us indoors. They wear patchwork clothes and hand-stitched hides. They come from all across America, but have found new homes in rural communities (like the queer eco-farms in Tennessee, Ida and Short Mountain Sanctuary), and float between free-thinking oases like Asheville, Olympia, the two Portlands and New Orleans.

I hear many stories about New Orleans: After Hurricane Katrina, thousands of punk kids travelled down to Louisiana to help clean up the mess. Many arrived before the National Guard or FEMA. Unofficial collectives did the majority of the work in the Ninth Ward, while the government squabbled over jurisdiction and responsibility. In the months and years that have followed, waves of young people have landed in the city to lend a hand. They talk about “Katrina mud,” the putrid sludge of sewerage, river silt and pollutants they scooped and carried bucket-by-bucket. They remember the plastic smell of the FEMA trailers, the shoddy and overpriced emergency shelter vans sent in as temporary housing. In some locations, they were parked row-by-row, surrounded by wire and kept under floodlights – America’s own refugee camps.

“I don’t think any other city would have drawn such a response,” Mel tells me. “New Orleans was a very important cross-over point for travelling folk. We had all spent time there, or had friends who did.”

“STOP THE CAR! I spotted a possum back there,” says Mel. She jumps out of the passenger side door and jogs up the mountain road to fetch her claim. It was the first piece of roadkill we found during our afternoon drive through the rollercoaster hill roads of

“STOP THE CAR! I spotted a possum back there,” says Mel. She jumps out of the passenger side door and jogs up the mountain road to fetch her claim. It was the first piece of roadkill we found during our afternoon drive through the rollercoaster hill roads of She returns with a rather toothy looking black-and-white creature.

The possum is hung in the tree back at Caleb’s house for later butchering, alongside several deer carcasses rescued from the dumpster of a nearby slaughterhouse.

LATER WE LOITER in Asheville’s main streets. It’s refreshing to see a community centre retained in the face of the Wal-Martization of America. We stop in at a bookshop to read zines, and then hang around the co-op food store talking to locals. We head to ‘the bins’, the discount per-kilo Goodwill outlet, where Mel finds some wool clothes for her forest-dwelling season (see photo, right).

LATER WE LOITER in Asheville’s main streets. It’s refreshing to see a community centre retained in the face of the Wal-Martization of America. We stop in at a bookshop to read zines, and then hang around the co-op food store talking to locals. We head to ‘the bins’, the discount per-kilo Goodwill outlet, where Mel finds some wool clothes for her forest-dwelling season (see photo, right).Our last stop of the night is the dumpster of an organic supermarket. Josh and Mel strap on headlamps and start pulling out bags of rubbish, tearing them open and digging through the trash. I stand by, wanting to help, but restrained by first-timer’s fright. I’ve seen the food they have at home – the unspoilt meats and vegetables, barely-stale bread loaves and just-overdue dairies, from which they create the most delicious and wholesome meals. But this dumpster session yields nothing but true rubbish, to my sensitive eyes anyhow. Josh finds about a kilo of shredded pork, unwrapped and flecked with chewing tobacco. He picks off the tobacco, sniffs at it, and declares it edible. At that point I feel uncomfortable and slink back to the car to wait.

Later, when they cook and serve dinner, Josh gives me a pork-free portion of vegetables he cooked separately. I’m sure they’re secretly offended at my comfortable city lifestyle.

No comments:

Post a Comment